This fall, the Wild Steelhead Coalition honored Lee Spencer’s remarkable work on behalf of wild steelhead with their Conservation Award. The award gratefully acknowledges Spencer’s many years of dedication to his unique role as guardian and advocate for wild summer steelhead on Steamboat Creek, an important tributary to the hallowed North Umpqua River. In his decades overlooking the creek, it is no exaggeration to say that literally thousands of wild steelhead have been allowed to safely rest and eventually migrate to their spawning gravel without fear of poachers because of Lee Spencer’s presence there.

Photo credits: Dave McCoy

Written by: Gregory Fitz

The Sentinel of the Big Bend Pool

For nineteen seasons, Lee Spencer has returned to the Big Bend Pool on Steamboat Creek. He arrives in the middle of May, just as the first wild steelhead begin to show up at the pool. He won’t leave until the rains of early winter arrive, filling and cooling Steamboat Creek enough to allow the wild summer steelhead holding in the Big Bend Pool upriver passage to natal gravel in the creek’s pristine headwaters. Some years that means late December. Other years he pulled the trailer out by Thanksgiving.

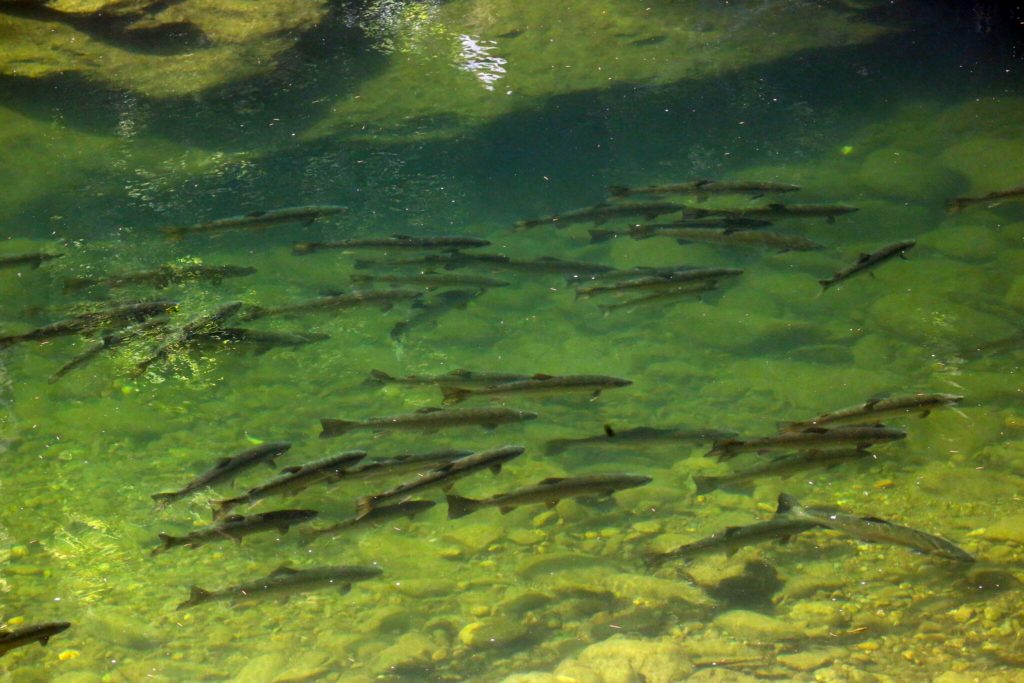

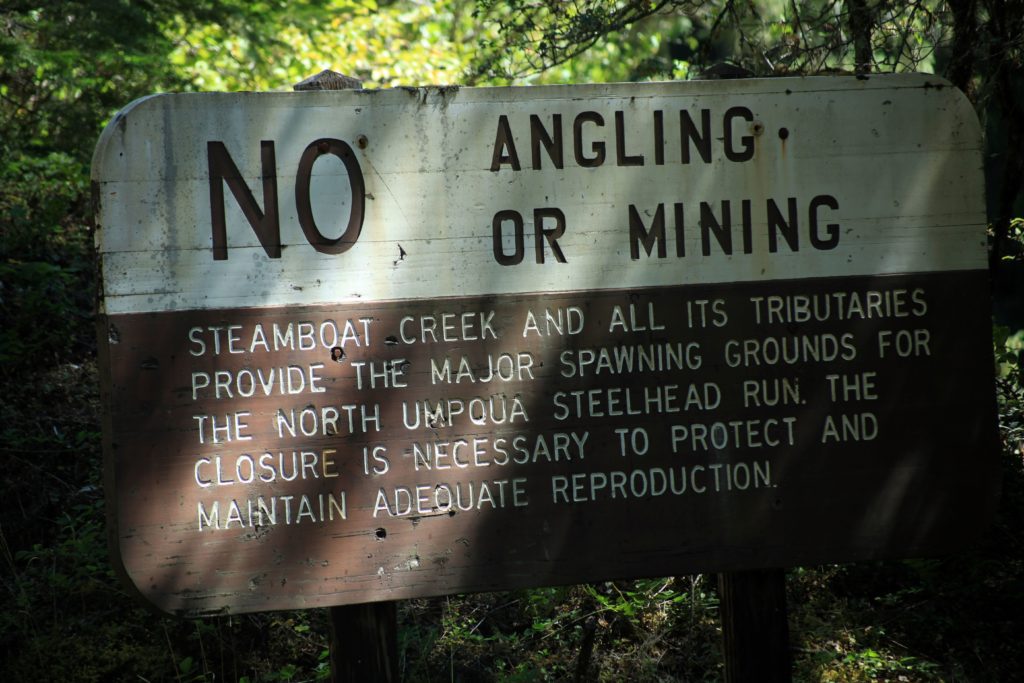

Steamboat Creek is an important spawning tributary to Oregon’s iconic North Umpqua River, but its flows run too warm during the heat of summer. The Big Bend Pool is 150 miles from the coast and 1600 feet above sea level. It is a crucial coldwater refuge where wild summer steelhead gather during their upstream migration. They can easily be there months, conserving energy and patiently waiting for the cooling rain. Between 400 – 800 wild steelhead will hold there each season. Locally, the Big Bend Pool was known as The Dynamite Hole because of how often explosives were used by poachers to kill the holding fish. Lee Spencer has been there all these years to make sure this doesn’t happen any longer.

Fishing has been illegal on Steamboat Creek since 1932, but laws don’t stop poachers in such remote locations. The pool was last dynamited in 1992. Even when explosives weren’t used, fish were often netted or snagged from the pool. Year after year, river and fish advocates lamented the continued destruction and loss. Eventually, a series of volunteers started staying at the Big Bend Pool in an effort to deter the poachers with their presence. This effort was a step in the right direction, but still left unoccupied gaps in the schedule when poachers could, and did, strike. The North Umpqua Foundation helped coordinate the volunteer schedules in an effort to smooth out the time between vacancies. One of them was Lee Spencer. After a stint watching over the pool in the fall of 1998, one conversation led to another and it was soon decided that Spencer would take on the entire season the following year. To make it possible, the North Umpqua Foundation, with additional support from the U.S. Forest Service, supplied a modest wage and a camper. Spencer turned down other work and committed the time.

Spencer says that he signed on for that first season guarding the Big Bend Pool because it was the right thing to do. At the time, he had no inclination whatsoever that it could become the defining feature of the next twenty years of his life. But, if you went out searching for an ideal candidate for such a unique role, it might be impossible to find a better person for the job.

Spencer had spent twenty years fishing the North Umpqua before he became the guardian of the Big Bend Pool, sometimes getting on the water 50 to 100 days during a season. It is an understatement to say he’d grown to deeply love the river and its wild steelhead. After a season in the 90’s where he hooked 78 steelhead, but accidentally killed three because they’d taken the fly too deeply or been exhausted by the encounter, he began to exclusively fish with a muddler minnow made of spun moose hair, the ends of the hair burnt by a lighter, tied on a hook with the point cut off and smoothed with a file. Cutting the hook’s point off had been his niece’s idea. Spencer fished it in heavy water with a riffle-hitch, and still does to this day, still thrilled by the dramatic effort of a wild Umpqua steelhead taking a skating dry fly, but without the potential impacts caused by hooking, fighting or ever touching the fish.

His dedication to this personal method of harm reduction is so deeply ingrained that when Spencer was invited to the Sustut River as a gift for his years of effort to protect the North Umpqua’s wild steelhead, Spencer surprised his friends and the other guests by continuing to fish his blunted hook. Over the course of that week on that beautiful water, one of the few times Spencer has bothered to fish anywhere besides his beloved Umpqua, he rose a number of wild British Columbia steelhead to his skating muddler.

Spencer had been a field prehistoric archeologist for twenty-five years before he found himself looking over the Big Bend Pool each season. His training and experience of living and working in the field and carefully recording observations was a perfect background for his time at the pool. He began to compile meticulous notes and observations from the hours spent watching the holding steelhead. He noted plants blooming, visits from otters and birds and the reactions of steelhead, both subtle and dramatic, to human visitors. He counted the times steelhead have risen to examine a floating leaf and once saw a steelhead take a struggling bat from the pool’s surface. For years, the North Umpqua Foundation has provided funding for Spencer to type up his notes during the winter. This massive resource on steelhead behavior is posted on the North Umpqua Foundations’ website and is free for the public to access.

During his nineteen seasons at the Big Bend Pool, Spencer’s presence has undoubtedly kept thousands of wild steelhead from being killed. This was, and remains, the primary goal of his presence on Steamboat Creek. But a second, crucial, role also developed over the years. Spencer became an advocate for the importance of wild steelhead to the thousands of people who have visited the Big Bend Pool to see the fish. Some of the visitors were simply curious, some were anglers stopping by to look between time spent on the Umpqua’s famous water. They all came to see the pool full of wild steelhead and meet person who protected them. No matter their reason for visiting, Spencer was there to trade notes and educate. He took this role very seriously.

In those conversations, he took particular care to emphasize the difference between the wild fish and hatchery fish to anyone with misconceptions or misunderstandings. Spencer is a staunch advocate for the superiority of resilient wild steelhead and despises the inferior hatchery fish for their aberrant behavior and dilution of wild genetics through interbreeding. In a recent phone call, Spencer told Paul Moinester and I that his advice for anyone who advocates on behalf of steelhead is to always make the distinction between a wild and a hatchery fish whenever discussing steelhead. Every conversation, either with a fellow angler or a member of the public, is an opportunity to emphasize this important boundary. Given current hatchery practices, wild fish and hatchery fish should not ever be allowed to be considered interchangeable.

For years, stories about Spencer’s role at the Big Bend Pool had gotten out among steelheaders. Slowly, he became something of a folk hero. I first heard of this amazing man who lived on the river, protecting wild steelhead and fishing without a hook when I still lived in Minneapolis. Though he never set out to earn accolades, recently his life of dedication and perseverance has been especially appreciated and celebrated. Spencer was featured in the movie DamNation a few year ago. In 2017, Patagonia published his beautiful memoir of his first fourteen seasons at the Big Bend Pool. It is called “A Temporary Refuge: Fourteen Seasons with Wild Summer Steelhead.” It is a wonderful book and I’d encourage any fisherman or conservationist to read it.

When the Wild Steelhead Coalition named Spencer as the recipient of their Conservation Award, he joined the ranks of other notable, passionate advocates for wild fish in the Pacific Northwest such as Frank Moore, Bill Bakke, Shane Anderson and Bill McMillan. He accepted the acknowledgment with typical grace, then immediately requested that the award money be donated in his name to The North Umpqua Foundation in order to further support their work on behalf of his beloved river and its astounding wild steelhead.

One thought on “The Sentinel of the Big Bend Pool”