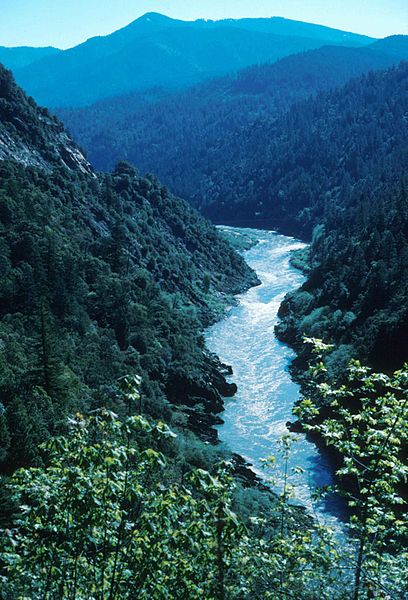

On a warm September Saturday in 2002, Amy Cordalis stood in a Yurok Tribal Fisheries Department boat on the Klamath River, in response to reports from fishermen that something was amiss on the river. On this stretch of the Yurok Reservation, the river was wide and deep, having wound its way from its headwaters at the Upper Klamath Lake, through arid south-central Oregon to the California coast. Cordalis, then 22, was a summer fish technician intern, whose job was to record the tribe’s daily catch. A college student in Oregon, she’d found a way to spend time with her family and be on the river she’d grown up with — its forested banks and family fishing hole drawing her back year after year.

Remnants of the fish kill lingered for weeks, as Cordalis and fishermen up and down the river looked on in shock. By the end of it, California and the Hoopa Valley, Karuk and Yurok tribes made a conservative estimate of the toll — 34,000 dead salmon along the Klamath — though officials said the sheer volume made a true count difficult. It was the largest fish kill in both Yurok and U.S. history, and its cause was no mystery. Earlier that year, the federal government had capitulated to public pressure from farmers and ranchers in the Klamath Basin and diverted water from the river to irrigate fields. The resulting low flows created a marine environment where fatal diseases could fester.

The Klamath water crisis and ensuing fish kill marked a pivotal moment for the Yurok Tribe. It shaped a generation of people, many of whom feel a fierce responsibility for a river that not only carries fish and water, but centuries of stories and struggle as well. As Amy Cordalis watched the salmon die, she told herself she would find a way to prevent similar tragedies. Today, she is the Yurok Tribe’s general counsel — meaning that, for the first time, the tribe has one of its own to lead its battles in court.

LINK (via: High Country News)

One thought on “How the Yurok Tribe is reclaiming the Klamath River”