Above the water’s surface, Hood Canal, Washington resembles a sportsperson’s paradise. From camping on the beach to hiking to rugged alpine lakes, to chasing deer and elk in thick timber, to foraging clams and oysters when the tide is out, outdoor opportunities abound in this verdant country. However, when you venture beneath the water’s surface and wade into the gorgeous, raucous rivers that carve up this stunning corner of Washington, you begin to see that something iconic is missing.

“Come for the clams and oysters, but don’t bother coming for the steelhead.” I stumbled across this haunting quote during the final dismal season of steelhead angling on Hood Canal. This quote turned out to be a harbinger of what was to come as Hood Canal rivers entered a long chapter of closure due to low returns of wild steelhead.

To many steelheaders today, the Hood Canal streams are just blue lines on a section of the map not worth exploring or knowing about. But to a whole generation of anglers, these streams hold a historic niche of local steelhead culture known only to the anglers fortunate enough to have ventured onto their banks, navigated through their sheer canyon walls, and made these rivers an indelible component of their lives.

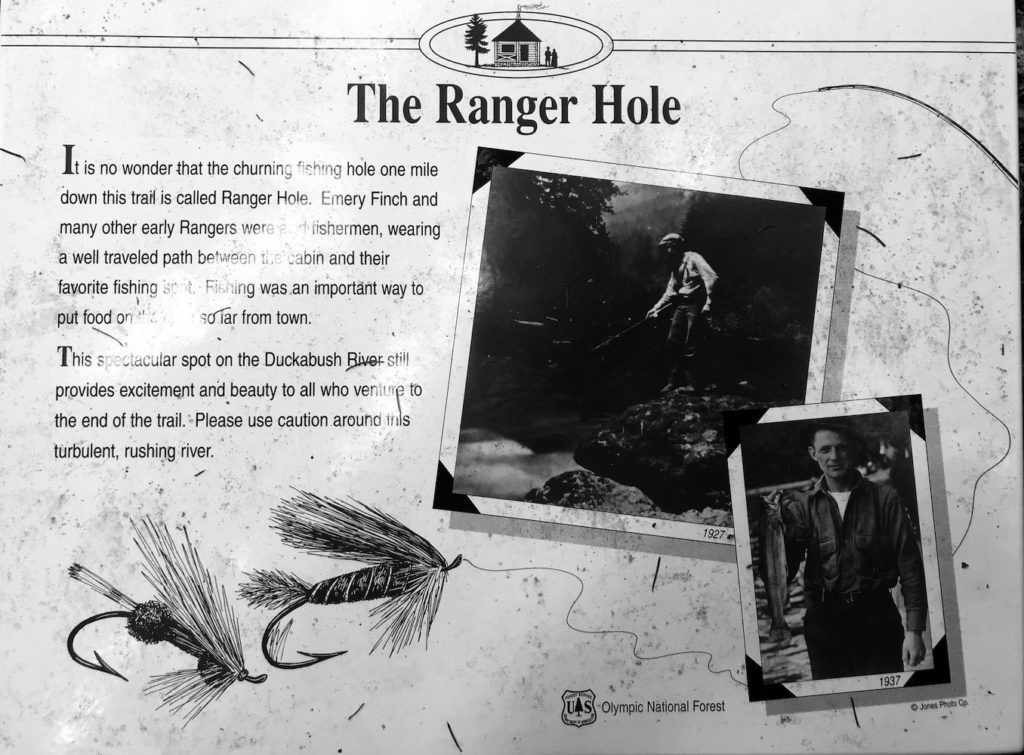

The special spots on this network of coastal streams were memorialized with monikers. The Ranger Hole on the Duckabush, the Skokomish’s Church Hole, the Blue Hole on the Hamma Hamma, and the Bridge Hole on the Dosewallips. These iconic steelhead pools were beautiful places where you would bank on seeing steelhead holding in clear, winter water and pray that one would accept your offering.

These days winter steelheading in Washington is a deep and dark affair done on big water and featuring heavy flies and lures, weighted lines, and invisible takes. But back in the heyday of Hood Canal, during a cold snap in the winter, you could sneak into the Duckabush and fish New Zealand style – sight fishing in crystal clear canyon pools to holding fish. Any take from a steelhead is memorable. But watching a steelhead track your offering, move towards it, and then take it is nothing short of magical.

Reading the tea leaves, it was clear the “Canal” streams were falling victim to the same problems that dealt a major blow to all Puget Sound rivers. It’s unbearable to watch a river’s run die, especially when you feel completely hamstrung to prevent that fate. But as painful as that is, in many respects it is even more painful to see how these once-beloved rivers have become invisible places to the present generation of anglers, who will never understand the wonders that once pervaded these waters or be filled with a desire to advocate for these rivers’ future.

Earlier this year, I hiked into the Ranger Hole brimming with hope that I might catch a glance at a pair of wild steelhead lazily finning in the tail out. It was eerily similar to those idyllic days of old. The water was gin clear and revealed all the beautiful structure I remember. Yet, there were no fish to be found. Perhaps I just walked in on a day when the fish were nosed into the frothing head of the hole and hidden from view. But the longer I stared at those barren waters, the more my optimism faded. I wanted so badly to see them again, but as is increasingly becoming the case these days, my steelhead dreams were left unfulfilled.

Much work and research are being done to better understand why Hood Canal’s steelhead are struggling and how we can bring them back. The work has been promising and research has illuminated that one of the biggest culprits of steelhead decline is the Hood Canal Bridge, which acts like a dam in the upper water column by temporarily blocking and disorienting migrating smolts, thereby making them an easy target for predators.

Fortunately, the habitat on these Hood Canal streams remains much better than in many Puget Sound rivers thanks to their greater isolation and their protected headwaters in Olympic National Park. One guarded bright spot includes some improvements on the “Skok”, where recovery efforts are inching along and runs are approaching escapement levels in recent years.

It is easy to lose faith after a lifetime of seeing the rivers you love struggle and die. But I still hold out hope that there is a future in which the Hood Canal rivers run wild with steelhead once again. A future in which I stroll into the Ranger Hole and see a dozen fish holding in gin clear water. A future in which my sons get to experience the magic of watching a wild steelhead track down and take a fly on a cold winter day.

But for that future to exist, we need anglers who never got to experience the wonders of these waters to fight for their future. And that long road to recovery starts by simply understanding what once was and by beginning to dream about what these rivers could become.

Hopefully, the seed for those dreams has now been planted.

Rich Simms is a lifelong steelheader who grew in the Hood Canal area and is a founding board member of the Wild Steelhead Coalition as well as Sage’s and Fly Fisherman Magazine’s Conservationist of the Year

A great read. Thanks.